Glittering Gold &

Colorful Enamel Glazes

Illuminated Medieval Mosques

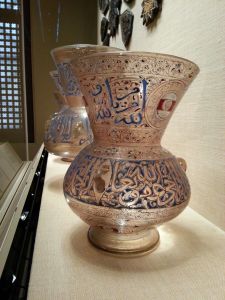

Mosque Lamp of Ahmir Ahmad al-Mahmandar, Egypt or Syria, Mamluk period (c. 1325, enameled and gilded glass) and others. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo by D. Feller.

Illuminated in their vitrines in a relatively dark gallery, the glass lamps created in Mamluk Egypt and Syria during the fourteenth century attract immediate attention with their colorfully enameled and gilded calligraphic designs. Among the ones displayed in gallery 454 in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, four line up in a vitrine against a wall, while in a case in the center of the room, a fifth appears with two non-lamp glass pieces.

Blue and gold, with accents of red and the occasional green and yellow, spell out Qur’anic texts and florid blessings related to the donor and those he served.1 Produced during the Mamluk period (and the previous Ayyubid one) primarily in factories in Damascus and Aleppo, decorated glass had been around for centuries. Building on advances in technique achieved during those years, Islamic craftsmen perfected a tricky process that required a different firing temperature for the colors than for the gold.2

Enameled and gilded glassware from Syria and Egypt, Mamluk period. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo by D. Feller.

This glassware from the Near East during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries acquired an international reputation, so much so that in the next century the renowned factories of Venice adopted what was probably the Syrian method. Closer to home, Syrian suqs abounded with multicolored examples fabricated by local artisans who also catered to Egyptian demand.3 A contemporary commentator wrote of glass items so wondrous in Aleppo markets that visitors did not want to leave.4

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, the invasion by the Central Asian Timur (also known as Tamerlane) devastated Syria, shattering the glassmaking centers in Damascus and Aleppo. Rumor had it that he also made off with the craftsmen. By 1500, trade in enameled glassware was totally reversed, with Venice now supplying the Mamluks.5

Such valued objects as those of fourteenth-century Syria would of course over time spawn knock-offs, and samples from the nineteenth century were particularly difficult to differentiate from originals until the conservation laboratory associated with the Musée du Louvre trained Raman spectroscopes on some Syrian glassware to identify the chemical composition of the colors used in known originals.6

Mosque Lamp of Sultan Barquq, Egypt or Syria, Mamluk period (c. 1382-99, enameled and gilded glass). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo by D. Feller.

As expected, lapis lazuli was used for blue and when mixed with Naples yellow, to derive green. Alternatively, cobalt blue was also used to make green. White came from tin oxide and sometimes calcium phosphate. These pigments differed significantly from those used by the nineteenth century imitators–arsenate white, cobalt blue and lead chromate yellow.7

To craft their masterpieces, Syrian artisans would first apply gold to the bare glass shape, using either a pen for lines or a brush for fill. Then a first firing would occur to fix the gold in place. Next came an outline of the design in red and the application of the other enamel colors, followed by another firing8 at temperatures ranging from 600 to 900 degrees Celsius.9 Since the gold and enamels required different temperatures to fuse with the glass, the trick was to find the sweet spot where colors wouldn’t run, the job would get done and the glass wouldn’t be compromised.10

Mosque Lamp, Egypt or Syria, Mamluk period (14th century, enameled and gilded glass). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo by D. Feller.

The resulting enameled and gilded glass lamps were hung on chains festooned with glass balls. Inside them, smaller glass vessels held oil, to be ignited when needed to illuminate the prayer hall.11 Inscriptions appropriately quoted the “Light Verse” from the Qur’an:

God is the Light of the heavens and the earth;

the likeness of His Light is as a niche

wherein is a lamp

(the lamp in a glass,

the glass as it were a glittering star)

kindled from a Blessed Tree,

an olive that is neither of the East nor of the West

whose oil wellnigh would shine, even if no fire touched it;

Light upon Light;

(God guides to His Light whom He will.)12

Elements of this poem form part of the inscriptions of at least two of The Metropolitan Museum’s lamps.13

Visitors enjoying the beauty of these objects are afforded a close-up view denied to worshipers for whom the lamps were originally intended, but undoubtedly afforded to like-minded connoisseurs wandering the stalls of a fourteenth-century Aleppo suq in search of a vendor to craft a lamp with inscriptions powerful enough to ensure the patron a place in heaven.

____________________________

1 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, online object information, accessed December 7, 2014, http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search?ft =Mosque+lamp.

2 Object label text, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

3 M. S. Dimand, “An Enameled-Glass Bottle of the Mamluk Period, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, no date but probably 1930s, 73.

4 Marilyn Jenkins, “Islamic Glass: A Brief History,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Fall 1986, 41.

5 Ibid.

6 CNRS (Le Centre national de la recherche scientifique), “Chemistry sheds light on Mamluk lamps,” press release, September 11, 2012, accessed December 7, 2014, http://www2.cnrs.fr/en/2109.htm.

7 Ibid.

8 Dimand, 74.

9 CNRS press release.

10 Object label text.

11 Dimand, 74.

12 Jenkins, 41.

13 Online object information.