Doing Together

What Can’t Be Done Alone:

An Integrative Approach to

Raped by Käthe Kollwitz

***********************************************

The Blind Men and the Elephant

by John Godfrey Saxe (1816-1887)

It was six men of Indostan,

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.

The First approach’d the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

“God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!”

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, -“Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ’tis mighty clear,

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!”

The Third approach’d the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

“I see,” -quoth he- “the Elephant

Is very like a snake!

“The Fourth reached out an eager hand,

And felt about the knee:

“What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain,” -quoth he,-

“‘Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!”

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said- “E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can,

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!”

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Then, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

“I see,” -quoth he,- “the Elephant

Is very like a rope!”

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

And all were in the wrong!

[1]

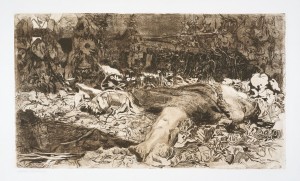

[1]Raped (Vergewaltigt) (1907/08, etching on heavy cream wove paper, 11¾″ x 20⅝″ [29.9 x 52.4 cm)]. Plate 2 from the cycle Peasant War. Proof before the edition of about 300 impressions of 1908. Knesebeck 101/Va. Photo © Kollwitz Estate.

One image, which looked like an ill-kept garden, revealed itself via the wall text to be a 1907/8 etching called Raped by a German artist named Käthe Kollwitz,1 who lived between 1867 and 1945. Viewers who took the time to look more closely would detect amid the foliage a woman with legs splayed and head thrown back, the subject of the picture’s title. At that point most would move on to look at other works. Some few would linger, wanting to learn more about this depiction of sexual assault.

The only other information available at that moment–the description nearby on the wall–identified the brown-ink print as a plate from the Peasant War series executed on heavy cream wove paper. Although unschooled in art historical methods, an intrigued viewer might intuitively know that much could be gained by exploring every aspect of this simply-framed etching.

Drawing the viewer’s immediate attention and bisecting the bottom of the almost-double-square (approximately 12-by-21-inch) composition, the woman’s foot–set off from lighter surroundings by its dark sole–meets the picture plane and beckons the onlooker to follow its arch to the foreshortened, thick-set leg that disappears under a skirt. The eye continues along an arc, through the torso and extended neck, stopping at the chin beyond which lies the shadowed face with its features distorted by the angle of view.

Searching for the rest of her, the observer discovers behind a bent-over, wilted sunflower the right leg, forming a horizontal line with the top edge of the skirt and ending in a foot that points toward the upper left corner. Assisted by a nearby still-upright flower slanted at an angle running parallel to it, the foot directs the gaze to a blossoming sunflower in the background’s deep shadow, the form of which echoes the head of a barely discernible child with a pony tail (or braid) who drapes her right arm over a fence and looks down at the body before her. Faintly silhouetted against a patch of open space, the young girl can easily be missed by all but the most attentive viewers as she blends in with the leafy plants around her.

Once noticed, the child leads the eye to a structure suggested by two sets of vertical lines hiding in the dark recesses of the upper register–perhaps a house. Across the rest of this small patch of verdant landscape, damaged plants and flowers tell a story of struggle and recent destruction in what might have been a well-tended, backyard vegetable garden.

A shadow originating from outside the picture plane on the left ends in a point that meets the prone woman’s right foot and relates to her dark skirt. Cast by a structure with straight edges and therefore of human origin, its top boundary becomes one side of a flattened diamond, the other three edges of which are the overgrown part of the fence that supports the girl, its dark extension to the right, and the left side of the woman on the ground. Ominous in nature, the sharply angled shadow seems a stand-in for the recently-fled rapist.

Following the perimeter of that diamond shape brings the inquisitive observer to the figure’s left hand, the fingers of which curl around the edge of her torn garment near some trickles of blood on her torso and provide the final clue to the story. A peasant woman working in her garden has been raped and stabbed, then left for dead. Hearing the commotion and perhaps some screams, her daughter has come to see what happened and now stares sadly at the sight of her mother, wondering what to do.

Having followed the trail of clues and figured out the narrative, the formerly-naive tourist, seduced by a compelling work of art, has unwittingly entered the empirical world of the connoisseur. Questions tumble forth about the decisions that went into creating the etching. Who was Käthe Kollwitz? What was the Peasant War and why did the artist choose it as a subject? Why did she make a print instead of a painting? If this is a series, what does the rest of it look like? Most curious, why didn’t Kollwitz just tell her story directly and not force her audience to work so hard?

As often happens in exhibits, another visitor approaches and, noticing the engrossed tourist with nose scant inches from the print’s protective glass, engages in conversation about the piece. An art historian by trade, the newcomer eagerly offers information about a favorite artist, her work and her art. An exchange ensues.

First they talk about the etching itself. When the tourist points out the little girl in the background and the trickles of blood near the victim’s left hand, the art historian is surprised, having never before engaged closely enough with the image to notice these elements. More concerned with Kollwitz’s subject matter in general and how it relates to the context in which the artist lived and worked, the art historian appreciated this new insight and resolved to be more attentive in the future to the object itself.

[2]

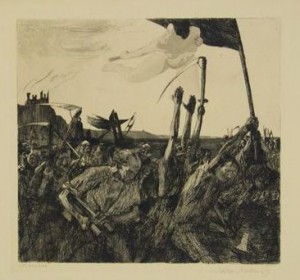

[2]Uprising (1902-03, etching on heavy beige wove paper, 20¼″ x 23⅜″ [51.4 x 59.4 cm]). Plate 5 from the cycle Peasant War. From the 1908 edition of approximately 300 impressions. Knesebeck 70/VIIIb. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY.

Familiar with most of Kollwitz’s oeuvre, this knowledgeable viewer knew that Raped was the second plate of seven in the print cycle Peasant War, commissioned by the Association for Historical Art in Germany following submission for consideration of the first completed etching of the series, Uprising (originally called Outbreak).2 In that print, a powerful woman, Black Anna, leads a contingent of fellow peasants armed with makeshift weapons against their feudal lords.3

[3]

[3]Revolt (1899, etching on heavy cream wove paper, 11⅝” x 12½” [29.5 x 31.8 cm]). First concept for plate 5 (Knesebeck 70) from the cycle Peasant War. Knesebeck 46/V. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, NY.

From childhood, when the young Käthe had enacted barricade scenes with her father and brother, she had imagined herself a revolutionary. It followed that as an artist she would draw strong women into her narratives, depicting them as they sharpened scythes, galvanized men into action, cared for the wounded and identified the dead. When Kollwitz read Wilhelm Zimmermann’s 1841 General History of the Great Peasants’ War and discovered Black Anna, an actual participant in the 1525 revolt by peasants against their overseers, the idea for this cycle was born.

Answering the tourist’s questions about Kollwitz’s choice of printmaking, the art historian explained that after struggling unsuccessfully to master color in her studies at a Berlin academy for women and later in a painter’s studio, and being introduced in 1884 to the work of master printmaker Max Klinger, the young artist finally gave up on painting and in 1890 took up etching, a technique at which she soon excelled. Although Kollwitz later devoted herself to the medium of sculpture, in which she modeled emotionally compelling figurative pieces, she never abandoned printmaking. Expanding her practice to include lithographs and woodcuts, she valued the reproductive capabilities inherent in these mediums, guaranteeing the widest possible audience for her socio-political ideas.

The composition of Raped differs markedly from Kollwitz’s usual images of women who are shown in active roles, not supine on the ground. It is also the only instance where she tackled landscape with enough details to identify cabbage leaves, sunflowers and other plants.5 As for its narrative, in correspondence about this print the artist referred to Raped as “the next to the last plate,” which would have made it the sixth out of seven (though it was published as Plate 2) and described it as “an abducted woman, who after the devastation of her cottage is left lying in the herb garden, while her child, who had run away, looks over the fence.”6

Knowing the artist’s intentions and how she came to etch Raped served only to whet the tourist’s appetite for more information. Just then someone else approached, walking directly up to the two viewers who were blocking access to the print. As chance would have it, the latest arrival turned out to be a psychotherapist who worked with trauma survivors and had a long-standing interest in art depicting sexual abuse and other forms of personal violence.

Käthe Kollwitz, whose work is permeated with meditations on struggle and death, naturally aroused the psychotherapist’s curiosity, especially with respect to how the artist came to focus on those themes. Joining the already in-progress discussion, the clinician related how the printmaker’s son, Hans, had nagged his mother into writing about her life and her development as an artist, and how despite her initial objections, she had surprised him with a manuscript in 1922 that he later augmented with diary entries and letters, and published in 1955.7 Hearing what had already been learned by exploring the image and its creation, the therapist added to the discourse aspects of Kollwitz’s psychosocial history crucial to understanding her choice of subject matter for the etching.8

In recounting her early years, Kollwitz described seeing a photo of her stoic mother holding her firstborn son, “‘the holy child,’” who had died within a year of his birth. Her mother lost a second son before Kollwitz’s older brother Konrad was born. When Käthe was nine, her mother had Benjamin, who also failed to survive beyond his first year, dying from the same meningitis that took the firstborn.

The artist remembered how one night, during her baby brother’s illness, the nurse had burst into the kitchen where her mother was dishing out soup and yelled that the infant was throwing up again. Her mother had stiffened and then went on serving dinner, her refusal to cry in front of her family failing to conceal her suffering from her young daughter, to whom it was obvious.

After that dinner, Käthe–with her younger sister Lise–was sent to play in the nursery where she built with her blocks a temple to Venus and began preparing a sacrifice to a goddess she had learned about in a book on mythology, and who she had chosen to worship over the Christian “Lord”–a stranger to her despite her family’s devotion to him. When her parents walked into the room to convey the bad news that her little brother had died, Käthe was certain “God had taken him” as punishment for her disbelief and sacrifice to Venus.

Because the family’s way was to grit teeth and carry on, with no discussion or even expression of loss and grief, Käthe carried the burden of guilt for her brother’s death into her adult years. Her mother’s unexpressed sorrow suffused their home and her oldest daughter lived in fear that her parents would come to harm.

Stopping the story at that point, the psychotherapist retrieved an ebook reader from a handbag and read from Kollwitz’s autobiography. “I was always afraid [my mother] would come to some harm…If she were bathing…I feared she would drown.” Reflecting on watching through the apartment window as her mother walked by, Kollwitz continued, “I felt the oppressive fear in my heart that she might get lost and never find her way back to us…I became afraid Mother might go mad.”

As the clinician tucked away the ebook reader, the trio of observers turned back to the etching Raped. Suddenly they understood what the artist might not have known herself, that the young girl looking over the fence was nine-year-old Käthe and the woman on the ground was her mother, finally felled by a trauma too insistent to be repelled.

As the three viewers continued contemplating the poignant image before them, another person approached. They eagerly began sharing their recent discoveries as they made room for the newcomer who, noticing the dates of the artist’s life, explained that Käthe Kollwitz was not a twentieth century artist but a woman born, raised and educated in the second half of the nineteenth century.9 Living in Germany in the late 1800s must have affected her art, they all agreed.

But that’s a story for another time.

____________________________________________________

1A print of the etching was displayed for a while in the Drawing and Print Gallery of The Metropolitan Museum of Art several years ago. The work under consideration, a proof, is in the private collection of the writer.

2Martha Kearns, Käthe Kollwitz: Woman and Artist (New York: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 1976), 85.

3See Elizabeth Prelinger, Käthe Kollwitz (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 30-39, for a description of the evolution and content of The Peasant War cycle.

4See Jane Kallir, “Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles” (Galerie St. Etienne, exhibit essay, October 8 through December 28, 2013) for additional information about Kollwitz’s print cycles.

5 Hildegard Bachert, “Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles,” gallery talk (Galerie St. Etienne, November 7, 2013).

6Käthe Kollwitz, quoted in Käthe Kollwitz: Werkverzeichnis der Graphik, by Alexandra von dem Knesebeck, trans. James Hofmaier (Bern: Verlag Kornfeld, 2002), 291. Relevant excerpt of text included in provenance documents accompanying the proof.

7The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz, ed. Hans Kollwitz, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1955).

8See Ibid., 18-20, for information about Kollwitz’s childhood experiences of loss.

9Bachert, gallery talk.

Käthe Kollwitz: The Complete Print Cycles

The Galerie St. Etienne [4]

24 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10019

(212)245-6734

Now till December 28, 2013.