Archive for January, 2011

Print This Post

Sunday, January 30th, 2011 Print This Post

Sunday, January 30th, 2011

Addiction Blog

Interviews the Artist

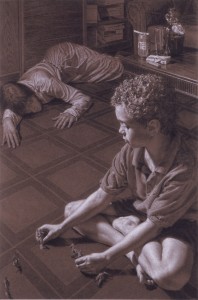

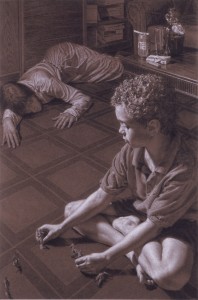

- Toy Soldier (drawing).

After discovering the drawings of Toy Soldier and The Annunciation in the publication Addiction and Art, Lee Weber decided to interview this artist to gain some insight into “[h]ow addiction counselors use art to heal,” a topic of interest to readers of the Addiction Blog.

The thoughtful questions posed focused on this artist’s early experiences with creativity and ongoing involvement with art as a force for healing and enlightenment.

Access the interview at the Addiction Blog.

- The Annunciation (drawing).

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post

Sunday, January 23rd, 2011 Print This Post

Sunday, January 23rd, 2011

Forever Young, Outsider Dalí

Danced with Old, Sparred with New

When photographer and friend Phillipe Halsman asked Salvador Dalí during a photo shoot, “Why do you wear a mustache?”, he received the response, “In order to pass unobserved.” When photographer and friend Phillipe Halsman asked Salvador Dalí during a photo shoot, “Why do you wear a mustache?”, he received the response, “In order to pass unobserved.”

Judging from the size of one of the massive crates required to ship his mural-sized paintings (revealed by an obliging museum guard in a behind-the-scenes peek) and the intense efforts Dalí expended to brand himself (long before anyone used that noun as a verb), he clearly intended that every endeavor generate attention, including the series of photographs that emerged from his work with Halsman.

Those Halsman-Dalí photos welcomed visitors to the High Museum of Art’s exhibit, Salvador Dalí: The Late Work. They combined portraits of Dalí with accompanying repartee. Following the question, “Why do you paint?”, and its answer, “Because I love art,” came an image of the artist with his mustache formed into an S turned into the American dollar sign with the addition of two paint brushes. Coins framed the face.

For only a time a Surrealist but forever associated with that movement, and famous for the melting clocks of The Persistence of Memory (1931), Dalí fell from grace early on because of his unapologetic commercialization of art. Assembled for the show at the High by guest curator Elliott H. King, a collection of Dalí’s late work aimed to situate this initiator of happenings and multimedia events, innovative sculptor, and expert draftsman and painter where he rightfully belongs: in the pantheon of great artists of the twentieth century.

In the first room of paintings, a vitrine contains Dalí’s copy of The Geometry of Art and Life by Matila Ghyka, opened to the page describing the Golden Section on which the book’s owner penciled notes that chronicled his efforts to understand it. In The Study for Leda Atomica (1947), Dalí inscribed a couple of phone handsets, a fully inked swan and Leda/Gala within an encircled pentagram, the construction lines for which intersect to divide into segments that relate to each other in accordance with the Golden Ratio.

Such geometric magic along with other scientific interests figured prominently in Dalí’s peculiar thought processes. The smashing of the atom, especially, captured his imagination and inspired depictions of disintegrating forms. Conceptualizing matter as reducible to an invisible state of energy suited Dalí’s philosophical and artistic wanderings in the insubstantial worlds of fantasy, dreams and the unconscious.

In addition to his prodigious visual output, Dalí wrote extensively on his favorite subject: himself. Among other topics, his musings expound upon his artistic choices, beginning with the paranoiac mechanism of his Surrealism days. Caught up in a multi-tracked train of thought, Dalí arrived at his Paranoiac-Critical mysticism, the underlying inspiration for much of the work in this exhibit.

Writing about his unique view of the world, Dalí aligned himself with paranoiacs who, he observed take “…advantage of associations and facts so refined as to escape normal people [to] reach conclusions that often cannot be contradicted or rejected and that in any case nearly always defy psychological analysis.”1 Indeed, this artist found relationships few others saw, morphing one object into another with his deft wielding of pen and brush.

Devoted to Dalí’s expeditions into the graphic arts, two rooms in the exhibit contained an array of styles and modalities that served as a good introduction to his extensive accomplishments in this arena. Unfortunately, late in his life he became fast and loose with his signature in a way that challenged future collectors and dealers in their attempts at authentication. On display, engravings from Ten Recipes for Immortality (1973) and colored lithographs from Don Quixote (1957) (both series inexplicably absent from the catalog) demonstrated Dalí’s expert draftsmanship. The High could do well to mount an exhibition devoted solely to this aspect of Dalí’s oeuvre.

Among the few early works included in the exhibit, Debris of an Automobile Giving Birth to a Blind Horse Biting a Telephone (1938) combined both Dalí’s paranoiac ability and his facility with both ends of a brush. On a dark ground, the artist scraped off paint to reveal form-defining lights and applied small dabs of color as highlights on the horse’s rump. With a radiator to its left, an automobile wheel in place of one of its forelegs and a fender over its other, this bio-mechanical animal bites down with a vengeance on a phone’s receiver, leaving the viewer to ponder what it might mean.

Dalí’s later works drew upon his fascination with quantum physics. In his Mystical Manifesto (1951), he unraveled the secrets of the Paranoiac-Critical approach and rallied aspiring artists to perfect their craft. When he wrote that the “mystical ecstasy is ‘super-cheerful,’ explosive, disintegrated, supersonic, undulatory and corpuscular, and ultra-gelatinous…,”2 Dalí included a reference to the quantum theory that energy exists in either wave (undulatory) or particle (corpuscular) form depending on the instrument used to observe it.

In an instructive example of his method, the Paranoic-Critical Study of Vermeer’s “Lacemaker” (1955), Dalí exploded his copy of the Dutch artist’s painting, at which he had spent an hour staring during a visit to the Louvre and then reproduced from memory (so the story goes). Insisting that he found four rhinoceros horns in Vermeer’s small image, Dalí included those in his updated version along with a recognizable face surrounded by strands and corpuscles of color and light.

The title of Saint Surrounded by Three Pi-Mesons (1956) directly references subatomic particles. Where others might see a person, Dalí utilized his paranoiac vision to reduce the holy figure to a mass of individual elements. This relatively small painting, housed in a protective glass-covered frame box, revealed a deftness of touch in the artist’s application of mostly grisaille daubs of paint interspersed with strokes of occasional blue in the face area and bronze on the hands. Golden tassels dangle at the bottom. An entire world exists in this assemblage of forms; reproductions barely hint at the effort required for its realization.

A devoted classicist, Dalí took issue with the art trends of his time. In a preparatory sketch for a page in his Fifty Secrets of Master Craftsmanship (ca.1948), displayed in the vitrine with the book on geometry, Dalí used parameters like “Grafmanschip, coleur, dessino” [all sic] to rate Mondrian, Picasso and himself alongside old masters such as Raphael, Leonardo and Velázquez. Picasso faired all right. Mondrian earned almost all zeroes, but so did Bouguereau.

Further expressing his negative feelings about nonobjective art, Dalí painted Fifty Abstract Paintings Which as Seen from Two Yards Change into Three Lenins Masquerading as Chinese and as Seen from Six Yards Appear as the Head of a Royal Bengal Tiger (1962), the name of which says it all. In the same room as that statement hung The Sistine Madonna (Quasi-grey picture which, closely seen, is an abstract one; seen from two meters is the Sistine Madonna of Raphael; and from fifteen meters is the ear of an angel measuring one meter and a half; which is painted with anti-matter; therefore with pure energy) (1958). A tromp l’oeil piece of paper and a cherry tied to the end of a string contrast in technique with the benday-dotted ear containing an image of a face.

Possibly one of Dalí’s most beautifully rendered paintings, The Madonna of Port Lligat (1950) showcases the wizardry with which this master could transform two-dimensional canvas into an imagined three-dimensional reality. With invisible brush strokes, Dalí lavished the same attention to detail on each object pictured. Brilliantly conceived, the Christ child that sits on the Madonna’s/Gala’s lap looks just like the neighbor’s kid, except for the end piece of a bread loaf that floats in the rectangular space carved into the youngster’s torso.

Two other floor-to-ceiling canvases deserve mention. In Christ of St. John of the Cross (1951), Dalí depicts the crucified figure from above, within an equilateral triangle, and suspends the cross high above a boat anchored in a large lake. Perhaps he intended the perspective to suggest God’s view of the event. Two other floor-to-ceiling canvases deserve mention. In Christ of St. John of the Cross (1951), Dalí depicts the crucified figure from above, within an equilateral triangle, and suspends the cross high above a boat anchored in a large lake. Perhaps he intended the perspective to suggest God’s view of the event.

Using a photograph of a horse’s head as reference, paranoiac Dalí noticed that the highlight on the creature’s neck resembled an angel. In Santiago El Grande (1957), the image reverberates throughout the huge painting. Over a blue latticework background, a rider mounted on a rearing stead hoists a golden cruciform figure. Fiery orange objects fly around in the uppermost lefthand corner. In the lower right, shrouded Gala peers out from behind her partly hidden face, confronting the onlooker with her one visible eye.

Not the last artwork displayed in the show but definitely a coda of sorts, The Truck (We’ll be arriving later, about 5 o’clock) (1983) captures the devastation Dalí suffered when his beloved wife and muse, Gala, died in 1982. Using a combination of oil paint and collage on canvas, this view from the inside of an opened-back truck alludes to “André Breton’s: ‘I demand that they take me to the cemetery in a removal van.’ The subtitle invokes Garcia Lorca’s ‘Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter’ (1935) refrain: ‘at five in the afternoon.’”3 Using a diluted brown and black wash, Dalí painted the interior with a seated figure silhouetted against a brightly lit exterior. A much darker mass close by looks like the painter at his easel, capturing the love of his life for eternity.

After Gala’s death, Dalí slipped away from life. His best work behind him, he spent the last years of his life an invalid. In 1989 when his heart gave out, the world lost a unique and gifted madman–and genius.

____________________________________________

1 “Selected Writings by Salvador Dalí,” Dalí, 2004, 550.

2 Ibid, 564.

3 Exhibit wall text.

Salvador Dalí: The Late Work

High Museum of Art

1280 Peachtree Street, NE

Atlanta, GA 30309

(404)733-4437

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Friday, January 21st, 2011 Print This Post

Friday, January 21st, 2011

Terrible Knowledge

-

Hasek (Alesandro Colla, right) confides in his Army buddy (Nathan Ramos, left) at the motorpool. Photo by Bobae Kim.

Reports and concerns about Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) resurface whenever the United States hosts returning soldiers from a war zone. Veterans afflicted with this condition, first described as shell shock (and war neurosis) during World War I, struggle with suicidal and homicidal impulses, alcohol and drug problems, disrupted sleep, intrusive thoughts and images, and other symptoms that put stress on their relationships and render even ordinary activities difficult if not impossible to perform.

In the intimate setting of The Drilling Company, a small off-off Broadway venue that provides an arena for quality productions not yet commercially viable, theater once again afforded a vehicle for exploring the impact of war on its survivors. Joining a long tradition dating back at least to the ancient Greeks (over 2,000 years ago), Eric Henry Sanders shined the klieg lights on a contemporary American war in his drama, Reservoir, a compact play requiring little in the way of staging and props, and able to dramatize its story with just a handful of characters.

The development of PTSD follows “…exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor involving direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury, or other threat to one’s physical integrity; or witnessing an event that involves death, injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of another person; or learning about unexpected or violent death, serious harm, or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate…”1

Further, “…the person’s response to the event must involve intense fear, helplessness, or horror…”2

And, “[t]he disorder may be especially severe or long lasting when the stressor is of human design.”3

In Sanders’s play, Frank Hasek (convincingly portrayed by Alessandro Colla) has recently returned from a first and long deployment in an unspecified theater of operations and can’t stop twitching and checking around corners for hidden threats. Andre (masterfully interpreted by Nathan Ramos), his buddy on the job at the vehicle repair shop on the military base, keeps his symptoms at bay through the wonders of modern chemistry and music piped into his ears.

Marisa, the mother of Hasek’s infant son, pleads, cajoles and finally takes it upon herself to set up an appointment for her oddly behaving partner to see a doctor at the Veterans Administration. Afforded a mere 15 minutes by an overwhelmed system, Hasek lucks out, finding himself in session with a more than understanding psychiatrist (finely acted by Karla Hendrik). Eventually he gets to tell his story, though that alone cannot cure his malady.

Ordered to participate in activities that result in the taking of innocent life, the knowledge that Hasek acquires about the behavior of ordinary people in life-threatening situations continues to haunt him long after he has left the scene. In writing the play, did Sanders have information about real events on the ground in what sounded like Baghdad?

Answering that and other questions in an interview,4 the playwright described doing research for the script by speaking with veterans, including one from the current war in Iraq and another from the historical one in Vietnam. The knowledge he gained from those conversations broadened his understanding of soldiers. He learned about the gruesome reality of life in a combat zone and that most young men enlist for economic reasons.

Originally basing the character of the emotionally wounded soldier on Woyzeck in the eponymous 1837 play by Georg Büchner and additionally inspired by contemporary interpretations of Greek battle tragedies,5 Sanders created Hasek as an amalgam of impressions gathered from his various sources. While the details might reflect actual conditions, the playwright deliberately avoided linking the events in his play to any specific soldier’s experience.

A self-described news junky,6 Sanders had noticed the similarity between the plight of Woyzeck and that of returning soldiers from Afghanistan, including reports of several who had murdered their spouses.7 Drawn to know more and apparently needing to share his newly acquired awareness, the playwright developed Reservoir which, despite numerous revisions, remained essentially the same as originally conceived.

Later in the play, when Marisa keeps her own appointment with Hasek’s psychiatrist, the doctor assures her, “It’s possible he can be the same person again.” But unfolding events onstage put the lie to that assertion and place audience members in the uncomfortable position of helpless bystanders as the ghosts that inhabit Hasek’s mind and control his life prevail, leading to even more bloodshed. Viewers, slow to leave at the play’s conclusion, must then grapple with their own vicarious traumatization.

Reservoir

The Drilling Company

236 West 78th Street

New York, NY 10024

(212)873-9050

____________________________________________________

1 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. American Psychiatric Association, 1994, 424.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Interview with Eric Henry Sanders, January 14, 2011.

5 Jonathan Shay, Odysseus in America, 2002, and Bob Meagher, Herakles Gone Mad, 2006.

6 Op cit.

7 Massachusetts Cultural Council, Three Stages, interview with Eric Henry Sanders, June 4, 2010.

Posted in Theater Reviews |

Print This Post

Thursday, January 13th, 2011 Print This Post

Thursday, January 13th, 2011

Color Comes to

Childhood’s Edge

An updated image of the painting Childhood’s Edge can be seen on the Work in Progress page. Work on the turquoise drapery in the background progresses.

Posted in Currently on View |

Print This Post

Monday, January 3rd, 2011 Print This Post

Monday, January 3rd, 2011

The Art of John Kelly:

Embodying Egon Schiele

A man rolls out a record player with a green felt turntable and spins a disk that plays period music while two other men enter, carrying identical signs that note defining moments in the all-too-brief life of Austrian artist, Egon Schiele.

In the next scene, the same man dances with a blank canvas, casting purple shadows on its white expanse, striking poses that capture the angularity of Schiele’s images, and focusing on fingers and hands that move of their own volition.

Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte, a combination of theater, dance, video and art, represents a culmination of 28 years of creation and reflection by John Kelly, the writer and performer who plays the young artist. Introduced to Schiele by an art teacher while attending Parson’s School of Design in the late 70s, Kelly fell in love with and then tried to emulate, often in self-portraits, the quality inherent in Schiele’s drawings, especially his line.1 The more he learned as he researched the artist, the greater affinity he felt for the man who drew and painted in Vienna during the second decade of the 1900s.

The artist Egon Schiele had the misfortune, in 1890, to be born into a family in the grip of a syphilitic father who refused treatment, infected his wife (11 years his junior) and gradually lost his mind to his disease, releasing the family when he died in 1904. Two years later, the 16-year-old Egon took his 12-year-old sister Gerti to Trieste on a trip that replicated their parents’ honeymoon.2 In 1912, charged with immorality and seduction for having under-aged girls model for him, Schiele spent 24 days in a local prison.3

Kelly captures that jail time in a video that cycles through the nights and days of his confinement. After an initial encounter with a guard who torches a drawing of a nude girl while a woman’s voice intones in German—perhaps the complainant in the case—the scene alternates between darkness and an overhead view of Schiele on his prison cot bathed in light. The positions he assumes as he tosses and turns echo his artwork, including one with outstretched arms like a crucifixion: the artist as martyr for his work.

In the onstage action that immediately follows, Kelly—wearing an undershirt—lies on the floor and becomes Schiele on the cot while his alter Egons dressed in suits walk around and mirror his movements. The tempo increases and when the Egons disappear, Schiele awakens as if from a dream to ponder the dance with his selves. The scene ends with a wall of stone projected on the screen replaced by his painting of four red-leaved trees. Out of pain comes art.

For Kelly, revisiting Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte provided an opportunity to rework the youthful version that grew out of his early days as an artist long before the success he enjoys now. Originally naming it with the more benign sausage knachwurst, he changed it to blutwurst (bloodwurst) because he found the latter more disgusting.4

To the originally physically challenging production that irreverently focused on telling the story—the truth—he added scenes and infused the entire performance with the gravitas that comes with maturity. The pleasure he experienced in the process surprised him; he didn’t know he would find the desire. The result exceeded his expectations.5

The scenes Kelly added to the original elaborate on Schiele’s relationships with women. First came Wally, a young woman he met in art school who became his model and lover. Then, after his release from jail and an eventual move to a new place, Schiele pursued a more reputable young woman, Edith, who later became his wife and the mother of his children.

Those familiar with Schiele’s paintings and life might have recognized Death and the Maiden, expressive of the artist’s desire to hold onto Wally despite his new marital status. In one scene, Schiele and his lover disappear behind a covered, tent-shaped form and re-emerge with the lifting of the drapery to reveal their faces in place of those in the painting. Life animates art.

Schiele’s wife Edith, the woman who had brought love and stability into his life, at six months pregnant succumbed to the 1918 flu, days before the artist did. In one of the most poignant scenes, the grieving Schiele confronts her body lying where she fell, draws a white chalk line around it, then retraces it, and tenderly, desperately, hugs various parts of her body.

Kelly’s additions and changes, including the ending scene of Schiele’s death, reflect a shift from youth’s blissful ignorance about relationships and their accompanying risks and losses to a more mature awareness of life’s vicissitudes. Browsing John Kelly’s website suggests a restless soul of many talents whose need to express himself requires a multiplicity of art forms.

Despite program notes that proclaim this as the definitive version of Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte, Kelly might surprise himself again in another 25 years with an urge to revise the piece, adding to and tweaking it from the vantage point of another quarter century of experience, growth and acquired self-knowledge.

______________________________________________

1 Interview with John Kelly, December 22, 2010.

2 Alessandra Comini, Egon Schiele, 1976, 10-11.

3 Galerie St. Etienne exhibit essay, “Egon Schiele as Printmaker,” 2009, 1.

4 Op cit.

5 Op cit.

Posted in Art Reviews, Theater Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, January 2nd, 2011 Print This Post

Sunday, January 2nd, 2011

Edward Hopper

Seeking Solitude in

Modern Times

- Edward Hopper, Self Portrait (1925-1930, oil on canvas, 25-1/4″ x 20-5/8″), Whitney Museum of American Art, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest, ©Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper.

A museum goer could easily miss it, tucked away in an alcove, the glass-enclosed wall display of two rows of photographs spanning more than fifty years of Edward Hopper’s life: at 21 in the New York Studio School, drawing the nude male model in Robert Henri’s class–fertile ground for the Ashcan School; sketching in Paris around the same time; years later, working on a watercolor of a Maine lighthouse; the older Hopper with his wife Josephine, whom he married at 42; his now older hands, etching; and at 76, sitting near the coal stove in his studio of many years, looking serious if not downright glum.

These pictures of Hopper belong to a cache of over 3,000 items bequeathed, upon the death of his wife, to the Whitney Museum of American Art months after the artist died in 1967. Since its founding as the Whitney Studio (and then Club) by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney in 1914, the museum has provided financial support and exhibition opportunities to a host of home-grown artists, including Hopper, and currently boasts a collection of American art the extent of which becomes apparent as one wanders around the exhibit, Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time, and thumbs through the accompanying catalog.

- Charles Demuth, My Egypt (1927, oil and graphite pencil on fiberboard, 35-3/4″ x 30″). Whitney Museum of American Art, purchase with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

The third venue for a show originally conceived as “a broad survey of American art from 1900-1950 that featured both realist and modernist artists…designed as an introduction for European audiences to American art of this period,”1 the Whitney decided to use its turn to focus “on the realist works that depicted modern life, both urban and rural, while also highlighting the artistic relationships that were most formative for Hopper…”2 On this side of the Atlantic, viewers enjoyed twenty more Hoppers (for a total of 32) as well as additional scholarship attempting to link Hopper’s art with that of his compatriots.

A quick walk-through of the exhibit, however, reveals that Edward Hopper operated in a universe all his own. Part of a group of urban-based artists who depicted city and factory views, folks at work and play, and other topics of life in the then new twentieth century, he labored from a deeply personal place.

The artist must have found validation in a Goethe quote he carried throughout his life:

The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me.3

Expanding on that, Hopper commented:

Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world. No amount of skillful invention can replace the essential element of imagination.4

Perhaps because the creative experience required encounters with his unconscious, Hopper often found himself stymied in his efforts to produce.

I wish I could paint more. I get sick of reading and going to the movies. I’d rather be painting all the time, but I don’t have the impulse. Of course I do dozens of sketches for oils–just a few lines on yellow typewriter paper–and then I almost always burn them.5

Nevertheless, and much to posterity’s benefit, many sketches did survive to become paintings, more than enough to provide an ample selection for the Whitney’s Modern Times exhibit and to be included in collections throughout the world.

In the show, a few early paintings by Hopper lack the skill so apparent in work a decade later. In Tugboat with Black Smokestack (1908) and Queensborough Bridge (1913), the subject matter generates more interest than the draftsmanship, composition, palette or paint handling, highlights of the artist’s mature work.

Though Hopper might not have yet developed his facility with the brush, a psychologically insightful composition rendered in conté crayon and opaque watercolor, Untitled (the Railroad) (1906-7), demonstrated that he could certainly draw. Peopling a bustling train station with an assortment of types performing a variety of actions, the artist focused attention on an unhappy looking child tagging along behind a woman, perhaps the mother, while a well-dress man boards the train.

- Edward Hopper, Soir Bleu (1914, oil on canvas, 36″ x 72″). Whitney Museum of American Art, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest, ©Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

With Soir Blue (1914), perhaps inspired by what he had seen on his three trips to Paris between 1906 and 1910, Hopper discovers the emotionally compelling world of color. At a terrace café, six individuals occupy tables while a woman with a painted face and low-cut dress stands erect in the background. Each distinctively pictured, as though a portrait of a personality the viewer should know–Manet (or Courbet) on the right? Van Gogh with the red beard?–none interacts with another, foreshadowing the isolation of the actors in Hopper’s later scenes.

In the primary-colored world of Railroad Crossing (1922-23), the wind, evident in the solitary tree in the foreground, sweeps over a diagonal road that leads the eye to the eponymous crossing. Barely noticeable in the shadow of a yellow house with blue roof and red chimney, a figure of a woman introduces an indeterminate narrative. The house, centrally located and flanked by two telegraph poles, has no visible neighbors.

Not surprising then that Hopper admired the art of, and became good friends with, Charles Burchfield,6 another realist whose work evolved into idiosyncratic depictions of town and country views devoid of human presence, like the two desolate winter street scenes included in the show. Each artist wrote about the other over the course of their lives.

- Edward Hopper, Seven A. M. (1948, oil on canvas, 30-3/16″ x 40-1/8″). Whitney Museum of American Art, purchase and exchange, ©Whitney Museum of American Art.

Absent inhabitants, classics like Railroad Sunset (1929), Early Sunday Morning (1930). and Seven A.M. (1948) imply an observer wandering alone while others gather elsewhere.

Edward Hopper, New York Interior (ca. 1921, oil on canvas, 24-1/4 x 29-1/4). Whitney Museum of American Art, Josephine N. Hopper Bequest, ©Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art.  Edward Hopper, South Carolina Morning (1955, oil on canvas, 30-9/16" x 40-1/4"). Whitney Museum of American Art, given in memory of Otto L. Spaeth by his Family, ©Whitney Museum of American Art. Paintings by Hopper that do include figures, like New York Interior (1921), Night Windows (1928), Gas (1940), South Carolina Morning (1955), and A Woman in the Sun (1961)–all in the show–come upon subjects engaged in solitary activities, oblivious to the onlooker who keenly watches them.

In searching for the perfect image to depict the ephemeral intersection of psyche and experience–reality filtered through the soul–Hopper found himself peering into the private moments of others and wandering around unpopulated locations. In the cacophony of modern times, he sought and perhaps finally found the freedom of existence inherent in solitude.

___________________________________________

1 Sasha Nicholas, co-curator, in a communication from the Whitney’s press office.

2 Ibid.

3 Quoted by Peter Findlay in Edward Hopper: The Capezzera Drawings, 2005, 2.

4 Ibid, 22.

5 Ibid, 14.

6 Barbara Haskell in Modern Life. Edward Hopper and His Time, 2010, 49.

Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time

Whitney Museum of American Art

945 Madison Avenue (at 75th Street)

New York, NY 10021

(212) 570-3600

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

|