Archive for November, 2010

Print This Post

Sunday, November 28th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, November 28th, 2010

European Art Between the Wars:

Pay No Attention to that

Rubble Behind the Column

In her thoughtful classic, Trauma and Recovery, Judith Lewis Herman addressed the fickle nature of society’s attention to the wounds of war (as well as to other human-inflicted assaults on individuals, like the sexual abuse of children).

Citing the medical community’s involvement in the treatment of “shell shock,” the diagnosis that emerged from the Great War, which conflated explosions’ concussive effects on the brain with the emotional damage inflicted by the horrors of trench warfare, Herman described how “[w]ithin a few years after the end of the war, medical interest in the subject of psychological trauma faded once again.”1

- Otto Dix, Skin Graft (Transplantation) from The War (Der Krieg) (1924, etching, aquatint, and drypoint, 7-7/8″ x 5-3/4″), The Museum of Modern Art, New York © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS).

It returned during World War II, disappeared soon after, then reemerged again with the United States’s military involvement in Vietnam, officially becoming Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in 1980. Now, Iraq and Afghanistan veterans’ struggles–both on battlefields and stateside–to manage their traumatic stress, once again challenges psychiatry to attend to the psychological wounds of war.

In keeping with humanity’s innate drive toward attaining pleasure and avoiding pain, and reeling from the devastation of a war that killed over 16 million and injured millions more, leveled cities and obliterated landscapes, what was left of the population of Europe retrenched, desperate to embrace any semblance of order.

In a masterful curatorial feat, Kenneth E. Silver dove into a sea of European art from the 20s and 30s and emerged with works to support his thesis about the resurgence of the classical ideal during those in-between years. In Chaos & Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918-1936, an exhibit at the New York Guggenheim Museum, he has chosen mostly paintings and sculptures, with occasional photographs and film, to highlight this unsurprising recoil from the intolerable reality of the ruins of the first world war. Silver interprets this turn to columns, monumental edifices and figures, and machine-inspired precision, as evidence of Europe’s compelling need to retrieve the grandeur of a much earlier period in Western civilization and forget about its capacity for mass murder and destruction.

Retreating from the free-wheeling creations of the pre-war avant-garde, culture in the years leading up to the next conflagration veered right in its insistence on constraint and conformity, and on adherence to newly established standards. A shell-shocked populace, artists included, hitched their hopes to rising stars who promised security but instead delivered up Fascism and Nazism, logical but disastrous consequences of suppressing difference and dissent.

The exhibit begins at the bottom of the building’s ramp, opens with Pablo Picasso’s Bust of a Woman and some words of his that set the tone for what ensues. “The art of the Greeks, of the Egyptians, of the great painters who lived in other times, is not an art of the past; perhaps it’s more alive today than it ever was. Art does not evolve by itself, the idea [sic] of people change, and with them the mode of expression.”

Following that, one can stroll into the nearby gallery and view a selection of 15 prints from Otto Dix’s Der Krieg (War), graphic depictions derived from personal experience of exploded buildings, mangled bodies, and other trench detritus. Reminders for those too eager to forget, these images refuse to participate in the collective denial epitomized by the balance of the work on display.

To strengthen the point of the exhibit, the curator omitted works by artists who, like Dix, insisted on portraying reality. In Germany, the prints of Käthe Kollwitz (Never Again War! [1924]) and Max Beckman (Hell [1919]), and almost everything by George Grosz, stand out as exceptions to the general trend presented here. Even Salvador Dalí, known for his self-serving, right-leaning politics, painted forebodings about Hitler (The Enigma of Hitler [1938]) and the Spanish Civil War (Soft Construction with Boiled Beans [1936]).

- Pablo Picasso, The Source (La source) (1921, oil on canvas, 25-3/8″ x 35-3/8″), Moderna Museet, Stockholm © 2010 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Although well represented with a number of paintings from his classical period, Picasso continued to march to no one’s drummer but his own. Appalled by the 1937 bombing of Guernica, that same year he lavished considerable creative energy on producing one of Europe’s greatest anti-war paintings, Guernica, in a distinctly nonclassical manner.

The art included in the exhibit after Dix, perhaps because of its regression toward the norm, mostly lacks depth and in many cases, craft. Interfering with the viewing experience, the architecture of the Guggenheim building forces the interested to stand some five feet from the paintings and ricochet between the elusive wall text and its distant referent.

- Mario Sironi, Leader on Horseback (Condottiero a cavallo) (1934–35, mixed media on canvas, 114-3/8″ x 108-1/4″), MART Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, Italy © 2010 Artists Rights Society (ARS).

Arranged in seven categories, roughly chronological, the exhibit takes the viewer upwards toward the rise of Hitler, Mussolini and Franco. The best of the work reaches back to Greco-Roman and Renaissance art for the sake of meaningful expression rather than for the glorification of Nazi and Fascist leaders, although in the final gallery illustrating The Dark Side of Classicism, Mario Sironi’s almost ten-foot-high Leader on Horseback (Condottiero a cavallo) (1934-35) excels in its ability to exploit the power of paint on canvas to aggrandize a military personage.

Self-portraits, like those of Carl Hofer (1932), Fridel Dethleffs-Edelman (1932) and Dix (1931), along with portraits by Alfred Courmes (Peggy Guggenheim [1932]) and, especially, Picasso’s Olga (1923) use a variety of approaches to excellent psychological effect.

Paintings by Marcel Gromaire (War [La Guerre] [1925]) and Barthel Gilles (Ruhr Battle [Barricade] [1929-30]) demonstrate that art could still convey the reality of war within the confines of existing styles.

An unusual sheet-iron figure, Antinous (1932) by Pablo Gargallo, while Greek in subject matter uses flat planes and lines to define a figure in space, deviating significantly from the other, far more representational, figurative sculptures.

The excellent catalog accompanying the exhibit convincingly links many European artists and their oeuvre with the rise of right-wing ideologues, some because of their own political beliefs, others out of expediency. Apparently little had changed since Greek and then Roman sculptors and painters served power hungry aristocrats and clergy, benefiting from the lucrative patronage.

One wonders what curator Silver might uncover after rummaging around in the art produced in Europe since World War II. Would he find European artists still turning to the rich and powerful for support and if so, what form does that patronage take now? While waiting for the sequel, viewers can enjoy the gems in this show at the Guggenheim and work off that frappuccino hiking up the ramp.

_________________________________

1 Judith Lewis Herman, Trauma and Recovery, 1992, 23.

Chaos & Classicism:

Art in France, Italy and Germany

1918-1936

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Muesum

1071 Fifth Avenue (at 89th Street)

New York, NY 10128-0173

(212)423 3500

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Sunday, November 14th, 2010 Print This Post

Sunday, November 14th, 2010

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt:

Sculptor of Pain

Many years ago in a mountain town in what is now Germany, a ten-year-old boy’s father dies and within months the child finds himself in an unfamiliar and urban environment after his mother moves the family to Munich to live with her brother. Soon after, the boy becomes an apprentice in his uncle’s sculpture studio. Years later as an accomplished portraitist, he produces over the course of 12 years a series of unusual heads that remain in his studio until after his premature death at age 47.

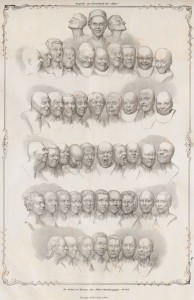

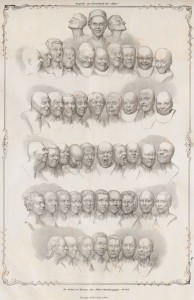

- Matthias Rudolph Toma (1792-1869), Messerschmidt’s “Character Heads” (1839, lithograph on paper), Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

Historical records provide little additional early biographical data on Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, the subject of that story and of an exhibit at the Neue Galerie, beyond those directly relevant to his artistic development. Born in 1736, by age 23 he had secured commissions from the royal family in Vienna, where he had moved six years before to study at the Academy of Fine Arts.

Hints of emotional instability surface by 1770, the year Messerschmidt’s financial success enables him to purchase a house in the suburbs. Coincidentally, that year also sees the death of his patron of 15 years, the artist Martin van Meytens (1695-1770). By 1771, at age 35, the sculptor’s life has unraveled.

Commissions have slowed to a trickle and the support he’s enjoyed as acting professor at the Academy evaporates. In 1774, when the Academy’s professor of sculpture dies, Messerschmidt–long considered his natural successor–finds advancement barred. The professors’ committee seizes this opportunity to free themselves of a man whose “…reason occasionally seemed subject to madness.”1 Further along the decision-making ladder, the State Chancellor reports that the artist is “not suitable for [the position]…because for the past three years he had demonstrated ‘some mental confusion’ and suffered occasionally from an ‘unhealthy imagination.’”2

During this period of time, in an attempt to prevail over his demons, Messerschmidt begins work on what will later be called–for lack of better understanding–“character heads,” sculptures depicting extreme facial expressions. His artistic talent and ability never desert him, as evident in the exquisite 1773-74? portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein.

- Prince Josef Wenzel of Liechtenstein (1773-74?, tin cast), Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein, Vaduz-Vienna.

In 1775, Messerschmidt attempts to relocate. He fails to find room at his childhood home, tries Munich for several years, then in August 1777, finds a place to live and work in Bratislava (now part of Slovakia) with his younger brother, also a sculptor. Within three years he has purchased his own home outside the city, where a brief illness thought to be pneumonia, ends his life in 1783.

The Neue Galerie’s exhibition, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783: From Neoclassicism to Expressionism, showcases both the skill and eccentricity of this artist. Greeting the viewer at the entrance to the show, an oval screen mounted behind a drawn picture frame, part of an ornately decorated wall, runs a video showing the “character heads” morphing one into another, looking for all the world like the sculptor posing in front of his mirror.

The first gallery presents work from Messerschmidt’s Early Years in a spacious room with white walls covered with outlines of Baroque paneling and intricate scroll work. Occupying a vitrine in the center of the mostly empty space, six portrait heads dating from as early as 1769, but also as late as 1782, establish the skill with which the sculptor captured images in marble and metal, and perhaps also the soundness of his mind.

Standing on its own in a corner, the portrait of Prince Joseph Wezzel of Liechtenstein, like the uncaged sculptures in later rooms, draws immediate attention by the power of its achievement. Metal becomes flesh and hair, bringing to life one of Messerschmidt’s first patrons.

In the second gallery, the viewer meets the artist transformed. A chorus line of seven heads in a long vitrine kicks off the intriguing subject of Messerschmidt’s Character Heads, his motivation for creating them, and his mental state at the time.

The impossibility of knowing the exact etiology and nature of the sculptor’s breakdown has not deterred the propagation of hypotheses, beginning with Friedrich Nicolai’s account of his 1781 visit to the artist’s studio. In a skeptical and condescending tone, Nicolai made observations and shared what he managed to extract from the reticent Messerschmidt.

He learned that spirits “frightened and plagued [the sculptor] at night,” pursuing him despite his having “lived so chastely.”3 Following a convoluted line of reasoning that Nicola valiantly attempted to record and explain, Messerschmidt arrived at the belief that “the Spirit of Proportion was envious of him because he came so close to perfecting his knowledge of proportions and for this reason caused him those pains [in his belly and thighs].”4

Further, the artist imagined that “if he pinched himself in various parts of his body, especially on his right side amid the ribs, and linked this with a grimace on his face which would have the same Egyptian proportion required in each instance with the pinching of the rib flesh, the height of perfection would be attained” and therefore protect him from the spirits.5

Nicolai came to his own conclusions about what ailed Messerschmidt as did Ernst Kris centuries later in his 1932 book on the sculptor, elements of which appeared in the 1952 English translation of his Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art.6 Each naturally brought to the endeavor his own point of view, not unlike the blind men and the elephant. Nicolai embedded his assessment in the rational thinking of his Age of Enlightenment and Kris wrote in the psychosexual language of Freudian theory.

The “character heads”—the best place to start in any analysis of Messerschmidt—tell their own story, speaking volumes about him. Unfortunately, because no one has yet found a way to date them, they can’t be used to track the evolution of his condition. Nor has anyone had the courage to alter the misleading and sometimes comical names given them after Messerschmidt’s death.

As a group, the “character heads” suggest a person in great distress. Although Messerschmidt referenced his own mirror image, only some approach self portraiture, the rest depict types. Most of the sculptures have eyes shut so firmly that folds and wrinkles accrue around them. The ones with wide open eyes stare blankly at nothing in particular, an effect enhanced by the absence of pupils. A few open their mouths but the majority close them tightly, hiding their lips. By way of explanation, Messerschmidt pointed out to Nicolai that “men must simply pull in the red of the lips entirely because no animal shows it.”7

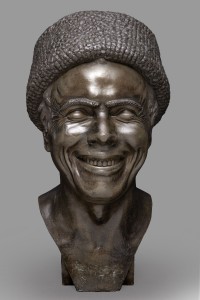

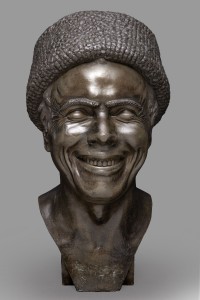

- The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing (1777–81, tin cast), private collection, Belgium

Messerschmidt’s suffering suffuses all his “character heads” including The Artist as He Imagined Himself Laughing. Closely resembling its creator, this sculpture presents a man in a lamb’s wool hat with a mouth open wide enough to show the top row of his teeth. As expected in any heartfelt grin, the action of the muscles that pull back the corners of the mouth push up the lower lids to cover the bottom of the eyes.8 That they come almost halfway up the eye belies the expression’s authenticity and provides evidence of the sculptor’s striking the pose for other than representational purposes, perhaps to openly challenge his demons.

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg) - The Difficult Secret (1771-83, tin cast), private collection, New York.

Anything but happy, The Difficult Secret expresses Messerschmidt’s pain in its eyes, where the action of the muscle raising the inner portion of the left brow pulls up the inner corner of the left upper lid.8 The downturned corners of the mouth, usually associated with disgust,9 coupled with the clenched lips, give the impression of grim determination. Each sculpture portrays Messerschmidt’s relentless battle to repel the evil spirits haunting him.

- A Hypocrite and Slanderer (1771-83, metal cast [lead-tin alloy?]), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Possessing one of the sillier names, A Hypocrite and Slanderer departs from the typical upright or slightly lifted head positions by tilting downward, requiring viewers to get on their knees for a complete view, raising the question of Messerschmidt’s own position while creating it. With the head retracting into the chest/body/self, this sculpture poignantly expresses the sculptor’s shame.

Messerschmidt could have unconsciously projected onto imagined evil spirits those impulses and emotions that his psyche found intolerable. Young children who lose a parent often blame themselves for the loss, remembering times when in a fit of frustration at a request denied, they wished their parents dead. For a child, the loss of a parent equates with abandonment and leads to diminished self-worth; after all, parents don’t leave good children. Without help, these children grow up harboring unanswered questions about early parental loss, and doubts about their own role in their parent’s death.

From age 19, Messerschmidt benefited from a relationship with the much older van Meytens, his early patron, perhaps more than just artistically and professionally. The 15-year bond with van Meytens provided an opportunity for the artist to receive care and attention from a father figure but might also have stirred up fears based on unconscious shame, guilt and rage from the long ago death of his father. In addition, the natural competition between student and teacher might have contributed to Messerschmidt’s projection of jealousy onto his demons following the man’s death, a manifestation of his guilt over seeking to best his mentor. Finally, consideration must be given to the possibility that the relationship with van Meytens had a sexual component, which would explain Messerschmidt’s lack of interest in women and his sexual conflicts.

When van Meytens died in 1770, Messerschmidt found himself awash in that little boy’s emotional turmoil. Adults who re-experience child feelings usually fear for their sanity because of the visceral and non-adult-like intensity of them. To preserve his ego, Messerschmidt regrouped by blaming his reactions on jealous demons who pursued him. Paranoid feelings can indicate projected guilt. When the paranoia overflowed into his work situation, the Academy had to get rid of him. Once again he found himself abandoned.

- Just Rescued from Drowning (1771-83, alabaster), private collection, Belgium.

- The Vexed Man (1771-83, alabaster), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

In two carved alabaster sculptures, Just Rescued from Drowning and The Vexed Man, Messerschmidt demonstrates his expert handling of the soft stone, incising impossible wrinkles to suggest aged skin and to emphasize the expression. With pursed lips, scrunched up noses, shut eyes and heads pitched forward, these old men anticipate imminent contact with something distinctly unpleasant. They brace for it and at the same time seem resigned to its inevitability.

- The Yawner (1771–81, tin cast), Szépművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

At first glance, The Yawner seems to be screaming, but a mouth that opens by lowering the chin into the chest impedes the flow of air in and out of the lungs, opposite of the maximum exhalation required for a scream. As for the work’s title, Darwin had this to say about yawning: “[It] commences with a deep inspiration, followed by a long and forcible expiration,”10 not possible under these circumstances. The vulnerability of the open mouth contrasts with the avoidance of the retracted tongue, squinting eyes, and nose wrinkled in disgust, indicating ambivalence–or more painfully, conflict–about the situation.

- Quiet Peaceful Sleep (1771-83, tin cast), Szépművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

The title bestowed by the anonymous author who originally named the “character heads” comes closest to accuracy in Quiet Peaceful Sleep. Here Messerschmidt has captured in a face devoid of the usual abundance of wrinkles an expression of peaceful resignation. Gently lowered upper lids close the eyes under a minimally knitted brow. The nose sits neutrally over a mouth that betrays some tension in its thinned upper lip, which rests on a full lower one. The expression brings to mind the state of the suicide shortly before an attempt, when despair has lifted enough to liberate energy for action; a calm descends on the victim who looks forward to final release/relief from pain.

For a full comprehension of Messerschmidt’s struggles, notice must be paid to the sculptures with bands across their mouths. If the tightly pressed and retracted lips in the rest of the heads fail to impress with their need to keep something in (or out), then slapping a strip across the mouth surely clarifies that intention.

Messerschmidt must have feared the power of his mouth to give voice to the taboo feelings he carried and perhaps also to divulge the true nature of his relationship with his early patron. Wrestling against that force, he left behind for posterity to ponder, beautifully crafted alabaster and metal portraits that continue to keep his secrets.

______________________________

1 Maria Pötzl-Malikova in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 21.

2 Ibid.

3 Frederich Nicolai, “Description of a Journey through Germany and Switzerland in the Year 1781, in Franz Xaver Messserschmidt 1736–1783, 208.

4 Ibid, 209.

5 Ibid.

6 Ernst Kris, Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art, 1971, 128.

7 Op cit.

8 Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face: A Guide to Recognizing Emotions from Facial Expressions, 1975, 104–5.

9 Ibid, 117–119.

10 Charles Darwin, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, [1872], 1989. 165.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783:

from Neoclassicism to Expressionism

Neue Galerie

1048 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10028

(212)628-6200

Catalog available.

Posted in Art Reviews |

Print This Post

Friday, November 5th, 2010 Print This Post

Friday, November 5th, 2010

Economic Bubbles

& the Brain

Like many people, Read Montague wondered about the inevitable cycles of boom and bust that plague economies. Being a neuroscientist, he devised an experiment to find out what happens in the brain when investors continue to pour money into businesses, real estate, stocks, and gold, despite the inevitable tumble destined to follow when values rise beyond reason during times of irrational exuberance.

An article in the New York Times Magazine described how Montague gave subjects $100 each to play a game where they invested in various market situations that unbeknown to them mimicked historical rises before crashes. During the game, Montague monitored their brain activity.

At the beginning, on the economic upswing as the players amassed profits, their brain activity showed nothing unusual. In keeping with the good feeling that accompanies gratifying experiences, neurons pumped out dopamine, the reward neurotransmitter. As subjects continued to benefit from the rising market, the dopamine increased their excitement and spurred on more investing as they scrambled for money.

After a while, something strange happened. Nearing the time the bubble would burst, the neurons slowed production of dopamine, as if to say, “Whoa, there!” Then just before the run ended, the dopamine neurons stopped firing completely. Rather than heed the cautionary feeling of that change in mood, investors continued putting money into the market, rationalizing the risks by reasoning their good fortune would go on forever. The prefrontal cortex, center of higher brain functions like cognition and self reflection, overrode the intuitive feeling in the rest of the brain.

Ordinarily, engaging cognition to manage emotional responses works out well. Apparently, there are times when thinking processes only serve to justify and defend behaviors that when considered from a different perspective, wouldn’t really make sense. The prefrontal cortex possesses enormous powers of self deception that can be tempered by paying attention to feelings, a valuable source of additional information.

Posted in Therapist Musings |

Print This Post

Wednesday, November 3rd, 2010 Print This Post

Wednesday, November 3rd, 2010

Psychiatry Treats Symptoms

Not Patients

Half of the adolescents treated for depression in a recent study suffered a recurrence of symptoms within five years. The study, reported in the New York Times, also found that girls were more likely to relapse than boys. The research protocol consisted of three options: an antidepressant, cognitive behavioral therapy, or a placebo pill.

About the results, the study’s lead author concluded, “It looks like we don’t have a treatment yet that really prevents recurrence.” In searching to explain the increased vulnerability of girls to relapse, he offered, “Maybe it has to do with something in girls…stressful life events or the way people cope with stress.” A doctor who was not part of the study suggested it might be linked to hormonal changes or that “women tend to brood more, so the slightest stress is multiplied many times.”

Doctors so caught up in the biological aspects of depression stray from the reality of life for teenagers in general, and the particular challenges faced by so many adolescents who have suffered various kinds of trauma: from childhood sexual abuse to living in violent neighborhoods, from loss of a family member to having serious medical problems. The list is, unfortunately, endless.

In choosing possible protocols, the researchers left out psychotherapy, that practice of engaging in conversation with the person who suffers. Instead, treatments were selected based on their uniformity of practice and hence replicability by others; psychotherapy does not lend itself to standardization because of its focus on relationship.

Meanwhile, the adolescents get lost in the process. The girls, more likely to have experienced sexual abuse than boys, get blamed for not being able to handle the stress in their lives. They “brood.” Perhaps the problem lies not with the teenagers but with adults unable to handle finding out what truly ails these young people.

Posted in Therapist Musings |

|

![Plate 18, The Difficult Secret [Front] for site](http://www.deborahfeller.com/news-and-views/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Plate-18-The-Difficult-Secret-Front-for-site-217x300.jpg)